by David Webster, Associate Professor, Department of History, Bishop's University

At a time when the Indonesian government seems to be clamping down on discussion of the mass killings of 1965, it’s more important than ever to share documentary evidence about the wave of violence that swept Indonesia 50 years ago and brought the Suharto military dictatorship to power.

The events of 1965 are not just an Indonesian story. In the words of a recent book co-edited by Indonesian scholar Baskara Wardaya SJ and international scholar Bernd Schaefer: “So far the international dimension of those events is hardly explored. Although they were domestic by execution, they were also firmly embedded into the global Cold War.”

Fifty years ago an army-led campaign of brutality targeted hundreds of thousands of Indonesians accused of being left-wingers in sympathy with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). The killings started with a coup and counter-coup, and were encouraged by the US embassy’s provision of names to the army. As U.S. government documents published in 2001 reveal, the Johnson administration had severed most American ties to President Sukarno’s government, preferring to work with the Indonesian army.

The true extent of American involvement in the Indonesian regime change and mass killings of 1965 is a story still to be written. Increasingly, there seems to be evidence that those once accused of being “conspiracy theorists” were right on many scores. Peter Dale Scott, a former Canadian diplomat who became a professor of English in California, is one of the most prominent of those figures, and has recently written a retrospective on his seminal article on US complicity in the events of 1965, forty years after its first publication.

Many State Department documents have been released. But many more remain hidden. U.S. government documents are normally declassified on a fixed cycle and the key documents published in the series Foreign Relations of the United States. When the time came to release the FRUS volume dealing with Indonesia in 1965, the government stalled on releasing of the volume.

That’s why ETAN has launched a campaign for a full declassification of all the United States government documents and a U.S. government acknowledgement of the American role in aiding and abetting the 1965 killings.

At a time when the Indonesian government seems to be clamping down on discussion of the mass killings of 1965, it’s more important than ever to share documentary evidence about the wave of violence that swept Indonesia 50 years ago and brought the Suharto military dictatorship to power.

The events of 1965 are not just an Indonesian story. In the words of a recent book co-edited by Indonesian scholar Baskara Wardaya SJ and international scholar Bernd Schaefer: “So far the international dimension of those events is hardly explored. Although they were domestic by execution, they were also firmly embedded into the global Cold War.”

Fifty years ago an army-led campaign of brutality targeted hundreds of thousands of Indonesians accused of being left-wingers in sympathy with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). The killings started with a coup and counter-coup, and were encouraged by the US embassy’s provision of names to the army. As U.S. government documents published in 2001 reveal, the Johnson administration had severed most American ties to President Sukarno’s government, preferring to work with the Indonesian army.

The true extent of American involvement in the Indonesian regime change and mass killings of 1965 is a story still to be written. Increasingly, there seems to be evidence that those once accused of being “conspiracy theorists” were right on many scores. Peter Dale Scott, a former Canadian diplomat who became a professor of English in California, is one of the most prominent of those figures, and has recently written a retrospective on his seminal article on US complicity in the events of 1965, forty years after its first publication.

Many State Department documents have been released. But many more remain hidden. U.S. government documents are normally declassified on a fixed cycle and the key documents published in the series Foreign Relations of the United States. When the time came to release the FRUS volume dealing with Indonesia in 1965, the government stalled on releasing of the volume.

That’s why ETAN has launched a campaign for a full declassification of all the United States government documents and a U.S. government acknowledgement of the American role in aiding and abetting the 1965 killings.

In the face of this withholding of information, it may be worth checking the files of more distant and less involved governments. Below I share some documents declassified by the Library and Archives Canada, part of the files of Canada’s Department of External Affairs. They reveal that Western governments had been aware of coup planning by the Indonesian army months before the actual coup; that Western governments did not initially believe the PKI was involved, but encouraged the army to attack the PKI regardless; that Canada’s government was one of those that did nothing to deter the mass killings – even with an estimate by the Indoensian ambassador in early 1966 that half a million people were already dead; and that the restoration of foreign aid to the new military regime of General Suharto was designed to anchor Indonesia into the Western side in the Cold War rather than aiming at humanitarian relief. Canada was a minor but well-informed player. Like other Western governments, it was pleased to see the Indonesian army take power, and indifferent to the enormous death toll that aided that path to power.

Many accounts depict the coup attempt of October 1, 1965, as a surprise that caught Western governments unaware. But in fact, coup talk had been around for some time. In June 1965, for instance, the prime minister of Malaysia informed diplomats from Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand that that Indonesia’s ambassador, a noted anti-communist, had told him that the army planned to get Sukarno out of the country and have him held hostage while it destroyed the PKI. PM Tunku Abdul Rahman said his information was that the Indonesian army “had decided time had come for drastic action to save country from Communist take-over. Army leaders were plotting to get Soekarno out of country and to hold him ‘if necessary at pistol point’ while army suppressed Communists and established pro-Western Govt.” The Tunku thought that the story might be fabricated, but also suspected the hand of the United States behind the army’s alleged plans.

DOCUMENT 2.

When, as September turned to October, soldiers led by Lt.-Col. Untung struck at the army command, capturing and killing top generals, General Suharto was quick to blame the PKI. Army-orchestrated massacres began soon after. The evidence shows that the “Old Commonwealth countries” put little faith in the claim that Untung’s coup was masterminded by the PKI. “As far as Brits could learn,” a Canadian diplomat in London wrote after meeting the responsible official at the Foreign Office, “Untung himself was not Communist and there was no firm evidence that Sep. 30 movement was inspired by Communists.” The British official reportedly told his Canadian counterpart: “Although it was tempting to believe that army would take advantage of present opportunity as excuse to deliver really crushing blow to Communists, unfortunately there were signs already that this was not likely to happen…” The hopes of the British Foreign Office, in other words, lay parallel to those of the US State department as already revealed in US documents – that the army would seize the chance to destroy the PKI. Their fears were that the army lacked the resolve or the capacity to carry out this task.

DOCUMENT 5.

In information-gathering about the coup, Canada’s mission in Tokyo similarly learned that the Japanese government assessment was also that there was no PKI involvement. “There was no evidence of sufficient prior planning to indicate organized effort by PKI,” a report stated. In a subsequent report, Japanese officials expressed a “low opinion of [the Indonesian army’s] admin[istrative] capacity and honesty” and predicted that they thought the army would do a poor job of governing Indonesia.

DOCUMENT 8.

Increasingly in the final months of 1965, the army command took the reins of government and encouraged violence against PKI members and others. By January 1966, the army-dominated government in Jakarta was ready to ask for foreign aid. The Canadian response to an Indonesian request to resume aid, which Canada had ended in 1964, was cautious to a fault. Ottawa planned to consult its major allies before acting, but noted that aid “might provide a means by which Indonesia could be drawn back into corporate international life.” Short-term relief, delivered ideally through the United Nations and its specialized agencies, might help ensure that the new regime in Jakarta would be pro-Western.

Many accounts depict the coup attempt of October 1, 1965, as a surprise that caught Western governments unaware. But in fact, coup talk had been around for some time. In June 1965, for instance, the prime minister of Malaysia informed diplomats from Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand that that Indonesia’s ambassador, a noted anti-communist, had told him that the army planned to get Sukarno out of the country and have him held hostage while it destroyed the PKI. PM Tunku Abdul Rahman said his information was that the Indonesian army “had decided time had come for drastic action to save country from Communist take-over. Army leaders were plotting to get Soekarno out of country and to hold him ‘if necessary at pistol point’ while army suppressed Communists and established pro-Western Govt.” The Tunku thought that the story might be fabricated, but also suspected the hand of the United States behind the army’s alleged plans.

DOCUMENT 2.

When, as September turned to October, soldiers led by Lt.-Col. Untung struck at the army command, capturing and killing top generals, General Suharto was quick to blame the PKI. Army-orchestrated massacres began soon after. The evidence shows that the “Old Commonwealth countries” put little faith in the claim that Untung’s coup was masterminded by the PKI. “As far as Brits could learn,” a Canadian diplomat in London wrote after meeting the responsible official at the Foreign Office, “Untung himself was not Communist and there was no firm evidence that Sep. 30 movement was inspired by Communists.” The British official reportedly told his Canadian counterpart: “Although it was tempting to believe that army would take advantage of present opportunity as excuse to deliver really crushing blow to Communists, unfortunately there were signs already that this was not likely to happen…” The hopes of the British Foreign Office, in other words, lay parallel to those of the US State department as already revealed in US documents – that the army would seize the chance to destroy the PKI. Their fears were that the army lacked the resolve or the capacity to carry out this task.

DOCUMENT 5.

In information-gathering about the coup, Canada’s mission in Tokyo similarly learned that the Japanese government assessment was also that there was no PKI involvement. “There was no evidence of sufficient prior planning to indicate organized effort by PKI,” a report stated. In a subsequent report, Japanese officials expressed a “low opinion of [the Indonesian army’s] admin[istrative] capacity and honesty” and predicted that they thought the army would do a poor job of governing Indonesia.

DOCUMENT 8.

Increasingly in the final months of 1965, the army command took the reins of government and encouraged violence against PKI members and others. By January 1966, the army-dominated government in Jakarta was ready to ask for foreign aid. The Canadian response to an Indonesian request to resume aid, which Canada had ended in 1964, was cautious to a fault. Ottawa planned to consult its major allies before acting, but noted that aid “might provide a means by which Indonesia could be drawn back into corporate international life.” Short-term relief, delivered ideally through the United Nations and its specialized agencies, might help ensure that the new regime in Jakarta would be pro-Western.

|

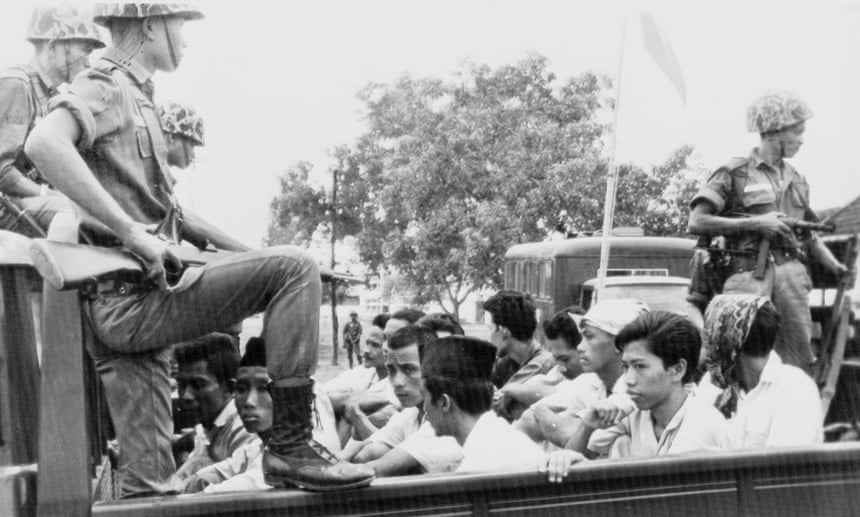

| Members of the Youth Wing of the Indonesian Communist party are guarded by soldiers as they are taken by open truck to prison in Jakarta, 1965. Photo: AP |

DOCUMENT 22.

What is striking in Canadian embassy reporting from Jakarta in the last months of 1965 and the early months of 1966 is the lack of attention to killings engulfing parts of the country. One embassy report opened with a declaration that the major challenges in Indonesian domestic affairs were led by high prices and inflation. Ironically, it took the Indonesian ambassador to Canada to put an estimate of the death toll of record. In his last call in Ottawa before being recalled to Jakarta, Ambassador L.N. Palar, speaking with “great frankness,” said that half a million people might have been killed by January 1966. Palar was one of the most respected members of Indonesia’s diplomatic corps – he had led the insurgent Indonesian independence delegation at the UN in the 1940s and then Indonesia’s UN delegation and been ambassador in Washington. His views, therefore, carried weight. His estimate was that the official estimate of 87,000 dead “was on the conservative side; speaking personally he would not be surprised if the tally came closer to 500,000.”

DOCUMENT 27.

This death toll did not alter Canadian views. Indeed, the Canadian ambassador in Jakarta, like U.S. colleagues, lamented the “passivity of [the] generals” in the face of President Sukarno’s efforts to remain in office. Canada, like its allies, hoped that the army would be more ruthless and seize power sooner rather than later.

DOCUMENT 31.

Days later, Indonesian generals forced Sukarno to sign the “11 March 1966 order” in which he handed real power to General Suharto. A representative was dispatched to stress to the British ambassador that the transfer of power was “gentlemanly” rather than brutal, and that “it would greatly help the Generals if this view could be taken abroad, rather than a renewed impression of lawless violence.” Britain’s man in Jakarta duly made that recommendation.

DOCUMENT 33.

In sum, the Canadian documents add to the weight of evidence that 1965 was an international story, as well as an Indonesian tragedy. Western governments were not surprised by events. They did not look on passively – instead, they encouraged the army to finish off its PKI rivals. They carefully used levers such as diplomatic pressure and foreign aid to support the result they desired: a military regime in Indonesia. And if that meant thousands killed, this was not bad news to the West, but simply the cost of bringing about the intended end of a pro-Western, army-governed Indonesia.

What is striking in Canadian embassy reporting from Jakarta in the last months of 1965 and the early months of 1966 is the lack of attention to killings engulfing parts of the country. One embassy report opened with a declaration that the major challenges in Indonesian domestic affairs were led by high prices and inflation. Ironically, it took the Indonesian ambassador to Canada to put an estimate of the death toll of record. In his last call in Ottawa before being recalled to Jakarta, Ambassador L.N. Palar, speaking with “great frankness,” said that half a million people might have been killed by January 1966. Palar was one of the most respected members of Indonesia’s diplomatic corps – he had led the insurgent Indonesian independence delegation at the UN in the 1940s and then Indonesia’s UN delegation and been ambassador in Washington. His views, therefore, carried weight. His estimate was that the official estimate of 87,000 dead “was on the conservative side; speaking personally he would not be surprised if the tally came closer to 500,000.”

DOCUMENT 27.

This death toll did not alter Canadian views. Indeed, the Canadian ambassador in Jakarta, like U.S. colleagues, lamented the “passivity of [the] generals” in the face of President Sukarno’s efforts to remain in office. Canada, like its allies, hoped that the army would be more ruthless and seize power sooner rather than later.

DOCUMENT 31.

Days later, Indonesian generals forced Sukarno to sign the “11 March 1966 order” in which he handed real power to General Suharto. A representative was dispatched to stress to the British ambassador that the transfer of power was “gentlemanly” rather than brutal, and that “it would greatly help the Generals if this view could be taken abroad, rather than a renewed impression of lawless violence.” Britain’s man in Jakarta duly made that recommendation.

DOCUMENT 33.

In sum, the Canadian documents add to the weight of evidence that 1965 was an international story, as well as an Indonesian tragedy. Western governments were not surprised by events. They did not look on passively – instead, they encouraged the army to finish off its PKI rivals. They carefully used levers such as diplomatic pressure and foreign aid to support the result they desired: a military regime in Indonesia. And if that meant thousands killed, this was not bad news to the West, but simply the cost of bringing about the intended end of a pro-Western, army-governed Indonesia.

etanetanetanetanetanetanetanetanetanetanetanetan

Help ETAN shatter the 50 years of silence concerning US complicity in

Indonesian violence. Sign, share http://chn.ge/1v50Edj

ETAN needs your support. Please donate today. Go to http://etan.org/Donate.htmSubscribe to ETAN's email lists